Recessions scar young people their entire lives, even into retirement

- Written by The Conversation

It is well-established that recessions hit young people the hardest.

We saw it in our early 1980s recession, our early 1990s recession, and in the one we are now entering.

The latest payroll data shows that for most age groups, employment fell 5% to 6% between mid-March and May. For workers in their 20s, it fell 10.7%

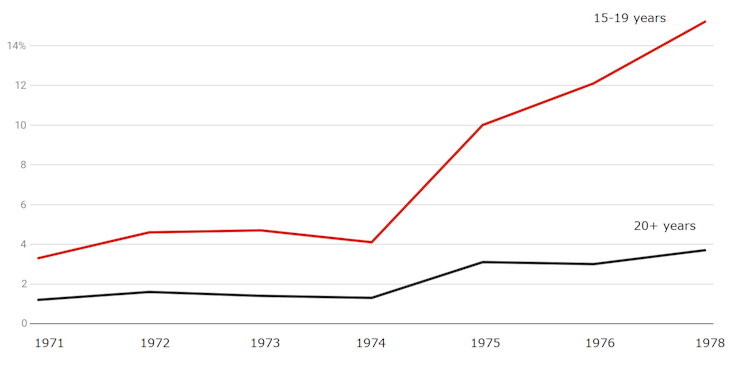

The most dramatic divergence in the fortunes of young and older Australians came in the mid 1970s recession when the unemployment rate for those aged 15-19 shot up from 4% to 10% in the space of one year. A year later it was 12%, and 15% a year after that.

Unemployment rates 1971-1977

ABS 6203.0

At the time, 15 to 19 years of age was when young people got jobs. Only one third completed Year 12.

What is less well known is how long the effects lasted. They seem to be present more than 40 years later.

The Australians who were 15 to 19 years old at the time of the mid-1970s recession were born in the early 1960s.

In almost every recent subjective well-being survey they have performed worse that those born before or after that period.

Read more:

There's a reason you're feeling no better off than 10 years ago. Here's what HILDA says about well-being

Subjective well-being is determined by asking respondents how satisified they are with their lives on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is totally dissatisfied and 10 is totally satisfied.

Australia’s Household, Income and Labour Dynamics survey (HILDA) has been asking the question since 2001.

In order to fairly compare the life satisfaction of different generations it is necessary to adjust the findings to compensate for other things known to affect satisfaction including income, gender, marital status, education and employment status.

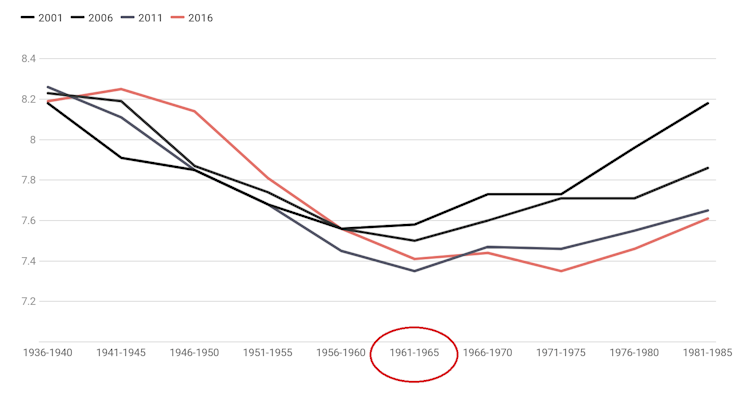

Doing that and selecting the 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016 surveys to examine how children born at the start of the 1960s have fared relative to those born earlier and later, shows that regardless of their age at the time of the survey, they are less satisfied than those born at other times.

Subjective wellbeing by birth cohort over four HILDA surveys

ABS 6203.0

At the time, 15 to 19 years of age was when young people got jobs. Only one third completed Year 12.

What is less well known is how long the effects lasted. They seem to be present more than 40 years later.

The Australians who were 15 to 19 years old at the time of the mid-1970s recession were born in the early 1960s.

In almost every recent subjective well-being survey they have performed worse that those born before or after that period.

Read more:

There's a reason you're feeling no better off than 10 years ago. Here's what HILDA says about well-being

Subjective well-being is determined by asking respondents how satisified they are with their lives on a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is totally dissatisfied and 10 is totally satisfied.

Australia’s Household, Income and Labour Dynamics survey (HILDA) has been asking the question since 2001.

In order to fairly compare the life satisfaction of different generations it is necessary to adjust the findings to compensate for other things known to affect satisfaction including income, gender, marital status, education and employment status.

Doing that and selecting the 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016 surveys to examine how children born at the start of the 1960s have fared relative to those born earlier and later, shows that regardless of their age at the time of the survey, they are less satisfied than those born at other times.

Subjective wellbeing by birth cohort over four HILDA surveys

Subjective well-being on a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 is totally dissatisfied and 10 is totally satisfied.

Regressions available upon request

The consistency of lower levels of subjective well-being reported by the 1961-1965 birth cohort suggests something has had a lasting effect.

An obvious candidate is the dramatic increase in the rate of youth unemployment in at the time many of this age group were trying to get a job.

Over time, labour markets can recover but the scars of entering the labour market during a time of sudden high unemployment can be permanent.

Read more:

The next employment challenge from coronavirus: how to help the young

The impacts of the early 1980s and early 1990s recessions on young people were alleviated somewhat by the doubling of the Year 12 retention rate and later by the doubling of university enrolments.

But the education sector is maxed out and might not be able to perform the same trick for the third recession in a row.

Reinvigorating apprenticeships and providing cadetships for non-trade occupations might help. Otherwise the effects of the 2020 recession on an unlucky group of Australians might stay with us for a very long time.

Subjective well-being on a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 is totally dissatisfied and 10 is totally satisfied.

Regressions available upon request

The consistency of lower levels of subjective well-being reported by the 1961-1965 birth cohort suggests something has had a lasting effect.

An obvious candidate is the dramatic increase in the rate of youth unemployment in at the time many of this age group were trying to get a job.

Over time, labour markets can recover but the scars of entering the labour market during a time of sudden high unemployment can be permanent.

Read more:

The next employment challenge from coronavirus: how to help the young

The impacts of the early 1980s and early 1990s recessions on young people were alleviated somewhat by the doubling of the Year 12 retention rate and later by the doubling of university enrolments.

But the education sector is maxed out and might not be able to perform the same trick for the third recession in a row.

Reinvigorating apprenticeships and providing cadetships for non-trade occupations might help. Otherwise the effects of the 2020 recession on an unlucky group of Australians might stay with us for a very long time.