Victoria's electric vehicle tax and the theory of the second-best

- Written by The Conversation

One of the central ideas in tax policy is the principle of the second-best.

Economic theory gives us a good idea of what an ideal tax system would look like, given our objectives. But in real life, things fall short.

It might be thought that piecemeal reform, moving some taxes closer to the ideal, would be a step in the right direction.

But it needn’t be, if other taxes aren’t moved.

Here’s an example. Imagine that the goods and services tax exempted health products, both mainstream and alternative.

An ideal GST wouldn’t exempt health products (though the government might provide subsidised access to some products, as it does through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme).

Imagine is administratively possible to remove the exemption for mainstream health products, which would bring it closer to the ideal.

Now imagine that for jurisdictional reasons it isn’t as easy to remove the exemption for alternative products.

Second-best can make things worse

Removing the exemption for mainstream products, which can be done straight away, seems like a good idea because it would be one step closer to removing all exemptions.

But if it is actually done straight away, without waiting the removal of the exemption on alternative products, it would have unintended (and perhaps dangerous) consequences.

People would be encouraged to switch from mainstream to alternative health products.

Read more: Think taxing electric vehicle use is a backward step? Here's why it's an important policy advance

The same sort of issues arise with the plans to charge electric vehicles per kilometre driven in order to treat them more like conventionally-powered vehicles (which are taxed per kilometre driven through fuel excise).

South Australia and NSW have announced plans to do so. Victoria has announced details, and will introduce the charge from July 2021.

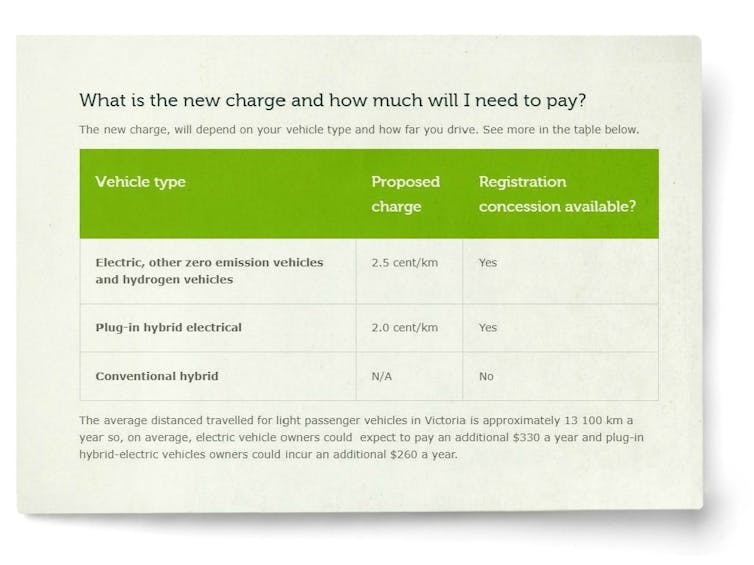

It will charge electric, and other zero emission vehicles 2.5 cents per kilometre travelled and plug-in hybrids at cents per kilometre travelled.

Victoria justifies the charge this way:

Australian drivers pay fuel excise when they fill up their vehicle with petrol, diesel or liquefied petroleum gas. Zero and low emission vehicle owners currently pay little or no fuel excise but still use our roads.

Conventionally-powered car typically pay about 4.2 cents per kilometre through fuel excise and fuel-efficient cars about 2.1 cents.

This means Victoria will be charging electric vehicles as much or more than fuel-efficient vehicles, even though (at least when charged through rooftop solar) they won’t contribute to global warming.

Not only that, but conventionally-powered cars generate health and other costs through air and noise pollution, for which they are not charged.

What first-best would look like

The ideal system would include charges to cover the cost of

building and maintaining the roads

congestion

the injury, death and damage caused by car crashes

the health and other damage caused by air and noise pollution

the global price of carbon emissions

Right now we charge through fuel taxes, registration fees and tolls (mostly paid to private firms, but this is irrelevant in economic terms) along with a variety of minor fees.

However, because fuel excise was frozen by the Howard government in 2001 (and only began increasing again in 2014) the revenue from it is barely enough to cover the cost of constructing and maintaining roads and grossly insufficient to cover the broader costs of conventional vehicle use.

Conventional vehicles get things for free

Although there is much debate about how carbon can or should be priced, any serious attempt to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement is likely to require a carbon price of $100/tonne, which corresponds to 23 cents a litre.

Estimates for local air pollution costs (including the cost of deaths from cancer and asthma) start at 10 cents a litre. Noise pollution costs are extra.

Electric vehicles powered by renewable energy generate hardly of these costs.

Put simply, just as much (or more than) the owners of electric vehicles, the owners of conventional vehicles pay a mere fraction of what they should.

Second-best would be worse

Increasing what the owners of electric-powered vehicles pay is a second-best solution that might move us further away from first best.

It might discourage the takeup of vehicles that impose fewer costs on society.

To end on a positive note, the 1997 decisions of the High Court that effectively prohibited states from taxing petrol forced the Commonwealth to collect the tax and pass it on to the states, exacerbating the problems of an unbalanced federal tax system.

Read more:

Wrong way, go back: a proposed new tax on electric vehicles is a bad idea

There appears to be no constitutional impediment to a tax on kilometres travelled (and nor a privacy impediment, Victoria will implement it by reading odometers rather than monitoring where cars travel).

It would help redress the tax imbalance.

It will charge electric, and other zero emission vehicles 2.5 cents per kilometre travelled and plug-in hybrids at cents per kilometre travelled.

Victoria justifies the charge this way:

Australian drivers pay fuel excise when they fill up their vehicle with petrol, diesel or liquefied petroleum gas. Zero and low emission vehicle owners currently pay little or no fuel excise but still use our roads.

Conventionally-powered car typically pay about 4.2 cents per kilometre through fuel excise and fuel-efficient cars about 2.1 cents.

This means Victoria will be charging electric vehicles as much or more than fuel-efficient vehicles, even though (at least when charged through rooftop solar) they won’t contribute to global warming.

Not only that, but conventionally-powered cars generate health and other costs through air and noise pollution, for which they are not charged.

What first-best would look like

The ideal system would include charges to cover the cost of

building and maintaining the roads

congestion

the injury, death and damage caused by car crashes

the health and other damage caused by air and noise pollution

the global price of carbon emissions

Right now we charge through fuel taxes, registration fees and tolls (mostly paid to private firms, but this is irrelevant in economic terms) along with a variety of minor fees.

However, because fuel excise was frozen by the Howard government in 2001 (and only began increasing again in 2014) the revenue from it is barely enough to cover the cost of constructing and maintaining roads and grossly insufficient to cover the broader costs of conventional vehicle use.

Conventional vehicles get things for free

Although there is much debate about how carbon can or should be priced, any serious attempt to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement is likely to require a carbon price of $100/tonne, which corresponds to 23 cents a litre.

Estimates for local air pollution costs (including the cost of deaths from cancer and asthma) start at 10 cents a litre. Noise pollution costs are extra.

Electric vehicles powered by renewable energy generate hardly of these costs.

Put simply, just as much (or more than) the owners of electric vehicles, the owners of conventional vehicles pay a mere fraction of what they should.

Second-best would be worse

Increasing what the owners of electric-powered vehicles pay is a second-best solution that might move us further away from first best.

It might discourage the takeup of vehicles that impose fewer costs on society.

To end on a positive note, the 1997 decisions of the High Court that effectively prohibited states from taxing petrol forced the Commonwealth to collect the tax and pass it on to the states, exacerbating the problems of an unbalanced federal tax system.

Read more:

Wrong way, go back: a proposed new tax on electric vehicles is a bad idea

There appears to be no constitutional impediment to a tax on kilometres travelled (and nor a privacy impediment, Victoria will implement it by reading odometers rather than monitoring where cars travel).

It would help redress the tax imbalance.

Read more https://theconversation.com/victorias-electric-vehicle-tax-and-the-theory-of-the-second-best-150936